LEICESTERSHIRE CLIMBSIntroduction and

History |

|

|

Leicestershire

Intro & History Grace Dieu Viaduct and Craglets |

INTRODUCTION It is usually thought that there is little or no

worthwhile climbing in Leicestershire. There are two reasons. The first is

that there really isn't a lot of climbing in Leicestershire and the second is

that the guide book to what there is has been out of print for many years. In this time much has happened. The longer climbs

are all in quarries to which the access is always changing; Huncote and

Whitwick are examples. Even worse, it has also become fashionable to fill

them in, and quarries such as Enderby, Barrow Hill and the lower tier of

Whitwick have mostly disappeared. Even though a guidebook has been in

preparation for many years such external factors have kept undoing the work

and preventing completion. Without the guidebook local knowledge has been

lost and once-popular crags have become overgrown and obscure boulders have

been "lost". A guidebook - any guidebook - has become an urgent

need. And here it is. Speed has been of the essence and it is a collation of

contributions of the many past editors over the years, but brought up to date

and revised with as much current knowledge as can be gathered quickly. There have been the usual discussions on what should

be included and these have mainly been decided on the availability of

information. This guide is not a comprehensive exposition on a developed

area, merely a holding operation. THE ROCKS OF LEICESTERSHIRE Leicestershire is a diverse county, geologically

speaking. The double landscape of Leicestershire - lush smooth valley

contrasting with the bare rugged uplands - is caused by very ancient

mountains of hard (in a physical, not climbing sense) old rock poking through

the more-recent marl deposits. The upland soil is thin and poor and is

frequently rough moorland or old oakwood. Charnwood Forest was described by

Burton in 1622 as "of hard barren soil, full of hills, woods, rocks of

stone, tors and dells of a kind of slate." Things have not changed much

and the ancient summits still have small crags and tors set in areas of great

scenic beauty. However although the rock is good, the climbs are short, rarely

being more than boulder problems. But the hard rock has also been of use

locally. The walls of the fields and old houses are built from it. There are

even slates on the roofs split from it. The places these useful stones

originally came from were the summits where the rocks were exposed. Sometimes

the quarries ate deeply into the hill, but usually the summits, as at Bardon

and Markfield, survived. Slate outcrops were followed downward into deep

pits. The quarrying of the ancient hills has left a network of old quarries

and pits in the hard rock areas of the county. So Leicestershire crags give bouldering on hilltops

and in woods and longer routes in the old quarries. There are two main rock types from the climbing

viewpoint - slate and granite, and both occur as natural tors and as

quarries. The natural tors of slate are usually in woods because the soil is

too poor for much else. The slate quarries are of modest scale, unlike North

Wales, and quite frequently flooded. They are sometimes very deep. The

granite also occurs as natural tors on some hills and almost every village

has an old small quarry, most likely called Parish Pit. The later Victorian

quarries were made possible by the cheap transport of the railways. They are

generally big and intimidating. Leicestershire was producing over a million

tons of granite a year by 1900. However, some quarries, such as Craig Buddon

which produced stone for a dam, are modest and could almost pass as a natural

crag. Recently the quarrying of stone has reached epidemic proportions and

absolutely massive quarries, square miles in extent, and hundreds of feet

deep have appeared. These new quarries have either eaten up the old quarries

or filled them in with overburden from land freshly prepared for quarrying.

None of the massive new quarries has yet been abandoned but it is obvious

that just transporting the fill to refill them will be an enormous nuisance

locally. With luck, they might survive and even leave some climbable rock. The reason that Leicestershire has so many quarries

is that there is no hard rock for roadstone etc. to the south-east. Leicester

granite is the nearest (and thus cheapest) hard rock to London.

Leicestershire produces 40% of the hard rock quarried in England, a vastly

disproportionate share. CRAG ORDER The climbing is concentrated in the hard rock areas

of Charnwood Forest and in a small area of hard intrusive rock south of

Leicester. There are many crags in this guide and putting them

into an obvious order is difficult. The crags south of Leicester (mainly

Huncote) form a natural group but the ones in Charnwood Forest (almost

everything else) would then be an overlarge group. The crags are listed in alphabetical order with a

group of minor crags under M. This is not ideal, but it is as logical as

anything else. Where a minor crag is near a major one, it is listed at the

end of the section on the major crag. Crag locations can be roughly obtained

from the area maps and detailed approach maps are usually given with the

entry. GRADING CLASSIFICATIONS Much has been written on how to grade climbs. In

this guide a combination of adjectival grades and technical grades is used.

The system follows that currently used in the BMC Peak District guides. The

sequence of adjectival grades is Moderate (M), Difficult (D), Very Difficult

(VD), Severe (S), Hard Severe (HS), Very Severe (VS), Hard Very Severe (HVS)

and Extremely Severe. The Extremely Severe grade is open ended; E1, E2,

E3...... . Technical grades identify the technical difficulty of crux moves

and the sequence is, in order of increasing difficulty, 3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, 4b,

4c, 5a, 5b, 5c, 6a, 6b, 6c, etc. Again, open ended. ROUTE OUALITY The system of stars, which has found wide

acceptance, has been followed. There are three stars for the best routes and

none for the worst. It should not be assumed that routes without stars are

not worth doing. It is merely that they have no star quality. A negative scale

(including black spots and daggers) is needed to identify the really

unfortunate routes, but this has not been done here. FIRST ASCENTS Where information is available the first

ascensionists together with the date of the first ascent have been recorded.

Where there are several claimants for the same route the Editors have done

their best (which wasn't much) to resolve the problem. CRAG AND ROUTE NAMES Some crag names have been changed, notably

Granitethorpe (previously Sapcote Ouarry), Whitwick Rocks (previously Peldar

Tor) and Nunckley Quarry (previously Kinchley Hill Quarry). Sapcote Quarry is

actually a different one to the climbing quarry and Peldar Tor is not in

Whitwick but along the road towards Leicester. Alternative names for crags have been given where

these are known. Because of the complexity of its ancient Precambrian rocks,

Leicestershire has a very rich geological literature. To relate the climbing

crags to the rocks in this geological literature you have to know what the

crags and quarries were once called. Carvers Rocks is a classic example. It

is never mentioned under that name in the geological literature. Some climbs have had multiple names because of

several claimed "first" ascents and also because routes were

renamed after aid was reduced. There is no perfect way of solving this

problem and again the Editors have done their best (so keep arguing about

it). ACCESS The major problem for climbers in Leicestershire is

access. The county is in a time warp with various interests trying to exclude

climbers. It's like the 30's. Even the public parks have not been without

problems. But it is the quarries with their extensive rock exposures that do

and will pose the greatest problem. The quarries are there to supply hard

rock aggregate to the populous South East. But this also means that for

climbers from the South East the Leicestershire quarries are the nearest

crags. This fact does not help access but is a prediction of potential

demand. AII land belongs to somebody (or some Company) and

they are legally entitled to deny access. THE INCLUSION OF A CRAG OR THE ROUTES UPON IT IN

THIS GUIDEBOOK DOES NOT MEAN THAT ANY MEMBER OF THE PUBLIC HAS THE RIGHT OF

ACCESS TO THE CRAG OR THE RIGHT TO CLIMB UPON IT. So far the crags have been lightly used, and whilst

a landowner may have tolerated infrequent visits by local people he may take

a different view if the numbers increase substantially. Under the Occupiers

Liability Act 1984 climbing is classified as a risk activity and the

landowner has no liability towards climbers unless climbing is conducted as a

business on the site (i.e. he charges). Under the most recent Mines and

Quarries Act and the Health and Safety at Work Act there is a legal

requirement for a quarry owner to exclude the public from his workings. There

is no prospect, with current legislation, of the BMC negotiating access

agreements to working quarries, even to disused faces. CONSERVATION Many of the crags in this guide are Sites of Special

Scientific Interest (SSSI's) and restrictions are imposed on the landowner by

English Nature on what can and can't be done. Other crags are in areas of natural

beauty or public ownership. Then there are the quarries - but if they are old

then even they are softened by the years. There is no reason why climbing and

the conservation of such areas should not co-exist if the usual good manners

of the countryside are complied with. So far the only problems in

Leicestershire have been connected with the numbers of visitors to areas and

climbers have been an infinitesimal part of these numbers. But with increased

use this may not be the case, and climbers using the crags should try to

minimise the effect of their passing. Where special restrictions apply they

have been noted in the text. CHIPPING, BOLTING AND PEGGING Many of the routes in this guide have been put up

with the minimum of fixed gear. It is hoped that the Bosch and dangle brigade

will not deface classic crags with bolts and pegs. This applies particularly

to Beacon H!II, Craig Buddon, Pocketgate Quarry and Hangingstone Quarry. Go

to Morley Quarry if you must. Remember the words of Geoffrey Winthrop Young

"Getting to the top is nothing; how you do it is everything". Even

Slawston Bridge has its ethics. On the first ascent of the traverse of Pipe

Wall a hold was chipped. When the route was subsequently done

"clean" the offending pocket was filled with Tetrion (exterior

grade, of course). Hence the name, Tetrion Traverse. This guidebook contains a lot of information. Whilst

a reasonable effort has been made to ensure accuracy it is obvious that

errors must be present. After all it is sixteen years since the last guide

went out of print. So don't regard any information (and that includes the

grades!) as gospel, treat it with circumspection. NEW CRAGS and NEW ROUTES (New

Routes) If you find a new crag (it's been known), or make a

new climb please send details, with dates (and these days, reliable

witnesses) to Ken Vickers, CORDEE, 3a De Montfort Street, Leicester LE1 7HG.

Details should also be written up in the New Routes Books which are held by

Roger Turner Mountain Sports, 52 London Road, Leicester LE2 OOD and Canyon

Mountain Sports, 92 Granby Street, Leicester LE1 1 DS. This guide owes most to the two previous Leicestershire

guidebooks edited by Ken Vickers. Many people have helped in getting and

checking the information in this volume; in particular: S. Allen, F. Ball, J. Bates, A Blowers, C.

Carrington, M. Chaney, J. Codling, B. Davis, I. Dring, S. Gutteridge, J.

Hart, M. Hood, T. Johnson, D. Jump, J. Lockett, G. Lucas, C. Maddocks, J.

Mitchell, J. Moulding S. Neal, R. Pillinger, R. Ramsbottom, A. Reynolds C.

Robinson, M. Sheldrake, P. Stidever, P. Wells and Bill Wright (BMC) There must be others whose names have been lost from

the various copies and rewrites of manuscripts. But getting the information

is not all. It still needed word processing into the format of this guide.

This was done by Gwen Massey and it is true to say that without her this

guide would not have seen the light of day. Thanks, Gwen, for such a

professional job and keeping cheerful through it all. Thanks also to

Loughborough University for the use of equipment and providing Library

facilities. |

|

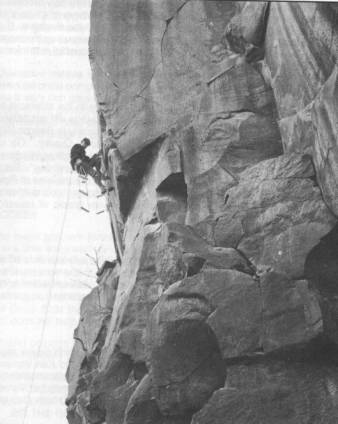

An example of what has been lost. This is

Cacophany in the old Enderby Quarry, taken in 1962, before the quarry was

filled in. The groove on the right was never climbed and Is now lost under

30m of rubbish and earth. This is Pete (Skully) Cross shortly before he fell

off, pulled out all the micro-pegs, and hurt his back. He now lives in

Australia. |

|

|

As the number of climbs in the country has

proliferated the idea of awarding stars for quality evolved so that the best

climbs could be identified. The system really needs extending to the crags

themselves rather than the individual climbs. For example: how does Stanage

compare with Lawrencefield? Or Cloggy with Dinas Bach? Or Stanage with

Cloggy? Leicestershire needs such a system because the range of quality of

the crags in this guidebook is enormous. The best crags are of national

importance and the worst are insignificant rocks buried in overgrown

woodland. In any assessment of crag quality it is obvious that the total

length of climbing is important, as also is the star quality of the routes,

together with atmosphere and pleasantness. One could discuss endlessly how to

do this, just like grading routes and awarding stars. As a first effort (and

it is quite good enough to assess the Leicestershire crags) we can award

"points" based on the number and length of climbs together with

their star quality. Each metre of climbing on an ordinary no-star route

counts one point. For a one-star route each metre counts two points, for a

two-star route It counts three points, and for a three-star route each metre

counts four points. When applied to the Peak District, a few selected

crags give the following approximate scores

For Leicestershire the list is as follows:

The obvious anomaly is that a brilliant, but

underdeveloped, crag would score zero points. In this guidebook Grace Dieu

Viaduct (with a possible 400 points) falls into this category. Bardon Hill is

lowly rated because it is so underdeveloped. A recent visit revealed that SHEET HEDGES QUARRY

(around SK526083), near Groby, looks as if it is about to be abandoned. This

granite quarry has been worked from mid-Victorian days to the present and

contains much rock exposure, a lot in long continuous faces. "Contains

more rock than all of the rest of Leicestershire" had been said. Hard to

believe if you've ever seen Bardon Hill. Further enquiries confirm that the quarry has

reserves for only another three years. However, planning permission has been

sought to quarry the causeway between the two pits. This is about 20 million

tons and would extend the quarry life by 40 years. Because the application

does not seek to extend the boundary of the quarry it is likely, but not

certain, that permission will be granted. Earliest reports of climbing in Leicestershire date

from the nineteenth century. Ernest Baker and Kyndwr Club members scrambled

on the limestone of Breedon Hill (see Moors, Crags and Caves, 1903). Not

surprisingly, quarrying has since erased their efforts. Climbing must have

taken place between the wars at Beacon Hill, Hangingstone Rocks and

Pocketgate Quarry but no record exists. The first recorded routes still

intact were the work of Peter Harding in 1945-46, who apparently climbed

"all obvious lines" on Carvers Rocks and Anchor Church Caves, which

must have included most of the existing routes up to VS. From 1949 to the

middle 50's, Peter and Barrie Biven, and Trevor Peck were active, their most

notable contribution being Christ (HVS,5a, now E1, 5b) on Hangingstone Quarry

in 1954, together with several classic problems at Beacon Hill, Hangingstone

Rocks, Bardon Quarry, and Bradgate Park. By 1959 Ken Vickers and Dave Draper had arrived on

the scene. They formed the nucleus of the Leicester Association of Mountaineers,

and were responsible for discovering and developing a number of crags, among

them being Craig Buddon, Markfield Quarry and Whitwick Quarry and the Sixties

were greeted with a steady flow of new routes from them and their friends.

These included the classic Virago (VS, now E1 ) on Craig Buddon, and the

first routes on Whitwick and Enderby Quarries. By the time the 1966 guidebook

came out The Brand and Huncote Quarry were established on the climbers' map,

and Hangingstone Quarry sported the area's first Extreme in Christ Almighty,

albeit with some doubt about the amount of aid employed. Several names came to the fore after publication of

the guide including David Cooper, Chris Burgess, David Holyoak, John Gale,

Godfrey Boulton and Roger Withers. Some were members of what had become the

Leicester Mountaineering Club, and all were keen on unearthing new routes,

sometimes literally. 1968 saw the ascent of Red Wall Arete (HVS, now gone) at

Whitwick, and a year later John Harwood freeclimbed the technical Stretcher

(HVS) at Huncote, then the most important climbing ground in Leicestershire.

Also at Huncote, David Cooper created the excellent Little Nightmare (HVS now

E1 ) and the immense Girdle Traverse (HVS), as well as many routes of lesser

quality. The early Seventies saw no great steps forward in difficulty, with

possible exception of Trespass (El,5c, now gone) at Whitwick, a fierce

problem which rated HVS in Ken Vickers' 1973 guide. In the realm of

bouldering, however, the Slawston Bridge era had arrived, giving the next

generation of climbers a material advantage in training facilities. The

hardest problem here at the time was an eliminate on the Pipe Wall by Chris

Hunter, still rated hard for 6a. From 1977 a group of Leicester University climbers became

the driving force, headed by John Moulding and Paul Mitchell. Partnered by

various combinations of Bob Conley, Stephen Boothroyd, Fred Stevenson and

Peter Wells, their campaign opened on Whitwick Quarry, which received a

number of new routes. Notable were Mr. Kipling's Country Slice (El,5b, now

gone), Freebird (E2,5c, now gone), a spectacular free version of The Nuts,

and Born To Be Wild (E3,6a, now gone), a very sustained crack line. Sadly,

all these were on the now-buried lower tier. Huncote gave its share of the

action in Heat Treatment (E2,5b), based loosely on the old Rack Direct, and

The Crimp (E3,6a,5c) climbed without recourse to aid. Hangingstone Quarry

became a minor forcing ground, with routes such as Weekend Warrior(E3,5b),

Christ Almighty free (E2,5c), and the superb Old Rock'n'Roller (E2,5c), the

free version of Cloister Groove. Moulding managed a flawed lead of Sheer

Heart Attack (E4,6a), using the only protection peg as a toehold.

Nevertheless, this remained for some time the hardest route in the county,

and is still regarded as a testpiece with a recent bolt for protection. It is

interesting to speculate on the origins of Holy Ghost (E3,5c) given its

ancient lineage and old grade of HVS. Also involved with development during this period were

Steve Gutteridge and Simon Pollard, both of the Leicester Bowline Club.

Pollard freed Three Peg Wall (E1 6a) on Carver's Rocks and Sorcerer(E1,5b) on

Forest Rock while Gutteridge created, amongst other things the , immaculate

Starship Trooper(6a) on Beacon Hill. Slawston Bridge stayed ahead in the

technical stakes with the Pipe Wall traverse at 6b/c. In 1981 Steve Allen and John Codling ushered in the

rnodern era, and within two years had accounted for most of the obvious

challenges. Climbing together and sharing leads, they were responsible for

first ascents, or first free ascents, of the following routes: Modular

(E4,6b) on The Brand, formerly A1; Arrows of Desire at Markfield (E3, 6a);

the extremely strenuous Sorcerer's Apprentice (E4,6b) on Forest Rock;

Catchpenny Twist (E3,5c, now gone) - a free climb based on The Plague, Tumble

Trier (E3,5c, now gone) and Pagan (E4,6b, now gone), all on Whitwick and a

stream of high quality lines in Huncote Ouarry. These include Firing Squad

(E4,5c), Eton Rifles (E4,6b), Intensive Scare (E4,6a) and the desperate Steeleye Span (E4,6b/c). Allen and

Codling were ' probably the first climbers to place protection bolts in

Leicestershire, at least partly because in situ pegs were prone to

disappearance. And so to the future. Despite access problems and

the steady encroachment by commercial interests on the remaining climbable

rock, new routes continue to appear. The working quarries are producing acres

of new rock but unfortunately modern blasting techniques shatter the rock

more than the older methods, leaving a less suitable medium for climbing in

the immediate future. This probably means that recently closed quarries may

provide scope only for the truly dedicated. However, some classic crags must

inevitably remain untouched by quarrying and Slawston Bridge will hopefully

resist weathering well into the next century - but maybe the Council will

straighten the bend in the road. |

|